the influence of aquatic biodiversity on the behavior of sea kayakers

Individual behavior is subject to sociological influences.

Using concepts such as Bourdieu's habitus, Pocciello's socio-cultural approach to physical activities, attention to non-humans and ecological habitus, we determine the extent to which kayakers are influenced by aquatic biodiversity. What are the behaviors induced by biodiversity, and what are the criteria of an ecological habitus? These questions are at the heart of our work, and we set out to answer them through four interviews with kayakers. Using the two criteria of an "environmentally friendly lifestyle" and a pronounced taste for manual trades and tangible goods, the results highlight a differentiation in the behaviours adopted by members according to their proximity to these criteria.

Linking habitus to socio-ecological behavior

The world's top decision-makers met for two weeks in November 2022 at COP 27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. This moment of exchange and decision-making concerning the whole of humanity, or almost, is indeed synonymous with the will of the world's leaders to move forward. However, we mustn't overlook the individual gestures made on a daily basis by each and every one of us. The aim of this work is to understand the behaviour of kayakers with regard to biodiversity.

Kayaking, its practitioners, its impact

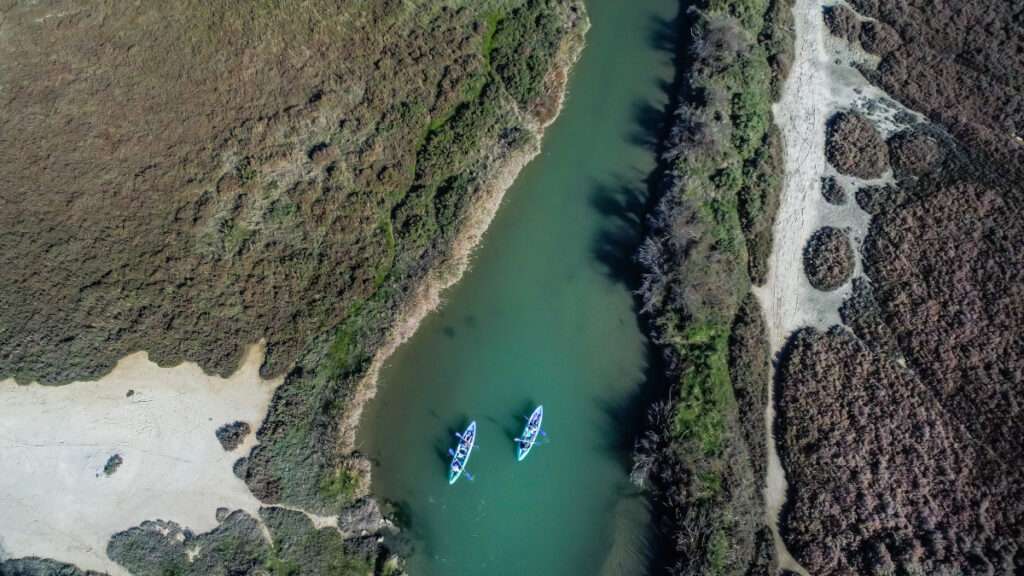

Nature sports have always been popular with the French. Indeed, the introduction of paid vacations in 1936 and the 35-hour working week in 2000 have given the French more free time, which is a factor in the "development of tourism and regular local leisure activities" (Vollet and Vial, 2018). Since 1945, they have been encouraged by Ministerial Instructions for outdoor sport: "Stimulated by the great outdoors and the natural environment, pupils are willing to make an effort". Dubuisson describes APPN (2009, p.1) as "characterized by the design and execution of a movement in a natural environment or reproducing it". Kayaking is a watercraft that allows you to cross aquatic environments rich in biodiversity, some of which are part of protected and preserved areas that are home to habitats and species representative of European biodiversity. Because the activity itself and the boats used respect these environments, kayakers are the only people who can get close to them.

Scientists are struggling to quantify the impact of kayaking on aquatic biodiversity. Mounet (2007) shows the gaps in research in a bibliographical analysis of 300 documents. He points out that scientists tend to deal only with emblematic species, forgetting "population dynamics", "the ecosystemic aspect" (p.5), and transport to the practice site. Finally, according to Bouthillier (2013), kayaking is "undoubtedly one of the only activities with minimal impact on the environment". On the other hand, the environmental disturbances he identifies are caused by the kayaker's behavior.

This is where a socio-cultural approach can be relevant to understanding behavior. Pociello (1981) conceptualizes a socio-cultural approach to practices, showing that sporting activities correspond to certain social classes. A social mix appears in certain sports, revealing different conditions for practicing the same sport.

Contact with non-humans in nature sports

Fauna and flora are what Rech and Paget call "non-humans" (Rech & Paget, 2017), a sociological notion developed by Latour. He states that when practicing a nature sport, movement will be hybrid, made up of interactions between humans, objects and non-humans: "We must accept the fact that the continuity proper to the unfolding of an action will rarely be made up of connections from human to human [...] or from object to object, but will probably move by zigzagging from humans to non-humans" (Latour, 2006, 108).

Rech and Paget add that "objects transform the course of an action and participate in new associations with humans" (2017, 8).

The relationship that each person has with the non-humans present when practicing an outdoor physical activity therefore takes on its full importance in the protection of the environment in which the activity is practiced.

The presence of non-humans in the practice environment is also of vital importance in the emergence of an "enchantment of the world" (Passavant, 2004). As Perrin-Malterre (2007) describes it, there is a state of enchantment characterized by wonder at the beauties of the world, a feeling of exaltation and inner quietude followed by a surge of affection. According to the author, this is favored by repeated physical effort, withdrawal into small groups and autarkic living in isolated regions. It's a phenomenon that can occur when kayaking. Indeed, kayaking is a sporting activity synonymous with repeated effort, whether for a single session or on a regular basis throughout the year, which can be performed alone or in a small group, and in isolated locations accessible only by kayak, creating the impression of being alone in the world, alone in autarky.

From habitus to ecological habitus

For this awareness-raising to take effect, it is important that this cause - the preservation of aquatic biodiversity - is a major concern, that it is present in people's minds. However, it appears that "ideological assumptions play an important role" (Myttenaere & d'Ieteren, 2009). Perception is inherent to each individual, and is influenced by multiple factors. It

habitus varies according to the reference group with which we identify, based on family, culture, shared values and social class. Bourdieu (1987) explains that habitus is a circular phenomenon that produces and reproduces the social conditions necessary for its reproduction. Indeed, a certain habitus will tend to lead to a certain habitus. Bourdieu (1980) defines it as a set of "structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures" (p.88). Thus, the habitus created by our experience and our surroundings, and formed during stages of socialization, is what makes us unique as human beings and social beings. This phenomenon triggers tendencies towards certain behaviours, which in turn become the basis for other behaviours conducive to the reproduction of this habitus. Indeed, habitus is not only the consequence of education, socialization and culture, it is also the cause of their replication, not identical but close. Wagner (2012) simply defines Bourdieu's notion of habitus as "a set of durable, acquired dispositions that consists of categories of appreciation and judgment and engenders social practices adjusted to social positions".

Some English-speaking authors use the Bourdieusian notion of habitus and link the combination of low economic capital and high cultural capital to "environmentally friendly lifestyles" (Carfagna et al., 2014; Holt, 1998; Horton, 2003). Pelikán et al. (2020, p.423) add that the habitus of this category of individuals is becoming more ecological, and their tastes are focusing on more tangible, sensible, local goods and manual labor: "The reconfiguration of high-status tastes concerns three dimensions: a new interest in materialism and the physicality of goods, a preference for the local and reverence for manual labor." (2020, p.423).

Debbie Kasper is not content with the notion of cultural capital; she goes further and develops the notion of "ecological habitus" (2009, p.312), a derivation of the Bourdieusian vision of habitus. Kasper indicates what ecological habitus refers to: "to the embodiment of a durable yet changeable system of ecologically relevant dispositions, practices, perceptions, and material conditions-perceptible as a lifestyle-that is shaped by and helps shape socio-ecological contexts"(ibid., p.318). The author believes that the concept of ecological habitus is a way of "rethinking" environmental behavior, but that it is important to create an empirical tool for studying, comparing and transmitting data on the "ecological habitus".

socio-ecological relations. "Socioecological" being a word used by Kasper (2009), referring to problems and phenomena often named "environmental", to implicitly convey the idea of relationships between "human social life" and the ecological contexts in which this takes place (2009, p.324). Kasper's aim, then, is to integrate ecological behavior into the concept of habitus. This research shows that the notion of biodiversity is not the same for everyone. It is specific to each individual and depends on our perception. As the latter depends on our own experience, our socialization, and various parameters such as education, cultural environment and the group with which we identify, it is constantly evolving. Bouthillier (2013) shows us that, despite the criticism levelled at tourism for degrading ecosystems, the kayaker has only a tiny impact on aquatic biodiversity, and adds that the kayaker's impacts are inherent in his or her behaviour and not in the exercise itself. All that's needed, she concludes, is to raise awareness and teach good practices. Ford draws on Kasper's work to declare that social practices are "not simply a matter of individual choice, but a reflection of social conditions that take place within systems of power "10 (2009, p.1). Our relationship with nature is therefore influenced by our sociological markers, but these can be modified by our experience of nature.

Indeed, contact with nature is central to our awareness of it as a whole. The idea of Leopold, an American ecologist of the 1940s, that outdoor leisure activities enable an encounter with nature, invites us to consider it as a living being in its own right. This "conscientization" or "critical consciousness" is a process of learning and discovering reality in order to free oneself from the oppression of social structures and habitus (Alexander et al., 2022: 3).

In this context, we are led to wonder to what extent socio-ecological behavior reflects an ecological habitus among kayakers. We hypothesize that kayakers with a high level of cultural capital are more likely to develop socio-ecological behavior than those with less cultural capital.

Methodology

Backed by a socio-ecological perspective on behavior, the survey, carried out in 2022 as part of a research dissertation (Vautier, 2021), was built on a qualitative approach with four members of Palavas Kayak de Mer. This type of data will enable us to develop certain topics such as childhood location and career path, in order to learn a little more about the subjects' various socialization processes. We're trying to understand the conditions, causes and consequences of the PKM kayaker's practice. With this method, we have gathered the opinions and experiences of our members, their motivations and addressed their concerns on the subject of aquatic biodiversity.

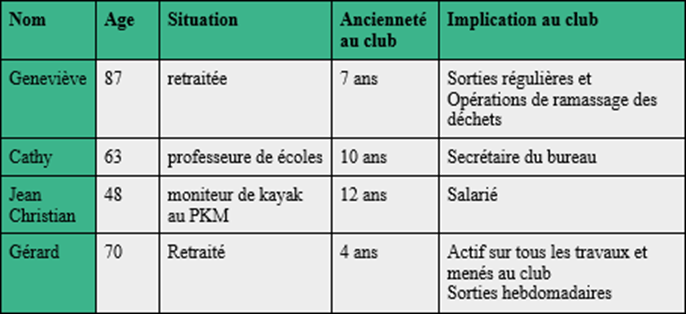

Our field of study is a fixed point, that of the Palavas Kayak de Mer club, but this is offset by a varied sample. The four members we will be interviewing have different practices. The richness of our survey lies in the plurality of the profiles interviewed and the different ways in which they practice. What's more, these members have different statuses at the club,

Some have been members for less than 5 years, others for more than 15. Some are simple members, others occupy or have an important function within the club. This gives us a broader picture of behavior based on involvement in sea kayaking. The heterogeneity of the profiles we interviewed is what made it possible to study a broad spectrum of behaviors that are interesting to study and analyze.

Thanks to our privileged position as an apprentice with Palavas Kayak de Mer, the method of individual interviews, face-to-face at the club, was a logical choice. We chose to conduct semi-directive interviews because, despite a fixed interview framework, the possibility of exploring certain themes or giving complete information according to personal verbatims remains present. We focused on childhood, followed by professional and sporting careers. We asked about the reasons for and conditions of practice, and the consideration given to nature. The interviews lasted between 20 and 40 minutes each and took place at Palavas Kayak de Mer, or by video interview (Cathy).

Palavas Kayak de Mer is an affordable club, open to all. We did not interview any children or young adults, but the sample faithfully represents the club. We have analyzed the different discourses of the interviewees, collected by a dictaphone and transcribed using the Ubiqus IO method.

Results

Here, we first present the results of our interviews with Cathy, Geneviève, Jean-Christian or Gérard, then analyze them along the spectrum of ecological habitus and different behavioral adaptations (contemplate, repair, avoid). We begin by studying our subjects through the prism of their "environmentally friendly lifestyle" (Carfagna et al., 2014; Holt, 1998; Horton, 2003), followed by their taste for manual trades. We then study the various behaviors of kayakers and compare them with the symptoms of a marked ecological habitus.

First of all, we'd like to point out that a survey of just a few members of this club of over 300 is not enough to establish a general trend. It is necessary to look at the behaviour of other club members who, although similar at first glance, are involved in a different activity. Indeed, the motivation to practice, the boat, the age or the skill level were not studied in their transversality during this survey. This raises questions about the different behaviours adopted by individuals who practice kayaking but have a less developed ecological habitus. This could be augmented by a larger-scale quantitative survey as part of a more comprehensive research project. However, in a study aimed at highlighting the biophilia hypothesis by quantifying the connection between humans and nature Cheng et al. (2020) recognize a particular difficulty; studying on a large scale how individuals interact with nature under different contexts.

Our four members are all over 40. We have two men, one working and one retired, and two women with the same distribution. Cathy and Geneviève are and were teachers; Cathy took the internal competitive examination after having her children, for the sake of stability. Gérard was a technician and moved up the ranks towards the end of his career, and Jean-Christian didn't use his BTS, took a series of odd jobs, then became a tattoo artist for 10 years before becoming an instructor at the kayak club. They all practice sea kayaking as a leisure activity, although Jean-Christian is the only one to go out on trips sometimes lasting several weeks. He is also responsible for sea kayaking at the club, giving lessons twice a week and organizing trips and tours. All four joined the club because they wanted to sail. Some like to practice exclusively in groups (Cathy and Gérard), while others prefer solo outings (Geneviève). Jean-Christian, whose level is much higher, also enjoys kayak surfing, bivouac treks and river descents. All of them speak of freedom when they describe their activities, whether it's geographical for Gérard, or a sense of freedom for the others. None, apart from Gérard, mentions the value of physical exercise, as if to emphasize, by omission, that the essence of their practice lies in the surrounding conditions. With different and sometimes incomplete definitions of biodiversity, our subjects seem to agree on a few different behaviors. Cathy mentions two verbs - "to see" and "to look" - and two nouns - "contemplation" and "gaze" - when asked how she pays attention to biodiversity. The other members also mention pre-practice information for

Some people (Jean-Christian) prefer to "minimize" their impact, while others advocate active behavior that aims to create an impact by repairing the environment. This is the case of Geneviève, who "picks up what there is to pick up".

As a derivation of the Bourdieusian habitus, which does not explore the environmental component, Kasper (2009) develops the ecological habitus, which she defines as "the embodiment of an enduring but also evolving system of dispositions, practices, perceptions and material conditions [...] shaped by and that shape socio-ecological contexts " 1. In so doing, Kasper integrates socio-ecological behavior with the notion of habitus. The results of our survey clearly show a particular sensitivity to the ecological environment among the kayakers we interviewed. Their behavior is modified to avoid disturbing the flora and fauna, and to enjoy and admire the beauty of the non-human environment that surrounds them as they paddle.

An ecological habitus

Environmentally friendly lifestyles

According to Carfagna et al (2014), the combination of high cultural capital - low economic capital can be linked to an "environmentally friendly lifesyle", which seems to be the case for our subjects. They have one thing in common: they practice sea kayaking as a leisure activity. What other elements can be found among the interview results that tell us whether our subjects have an "environmentally frindly lifestyle" (Carfagna et al., 2014; Holt, 1998; Horton, 2003)? First of all, Geneviève is a kayaker who, in addition to her conditions-perceptible as a lifestyle-that is shaped by and helps shape socioecological contexts"

moving silently, in authorized areas, makes litter-picking a habit and even a line of conduct in order to preserve the nature she cherishes. It's a habit that she reproduces on her own, or in a group, during litter-picking operations. This may have developed during her childhood, when her father, "very sensitive to the environment", would take her for walks in the Vosges, collecting mushrooms. Her outings are most often on the Mosson, in an area where the presence of birds is very strong. She also mentions a rare bird she was lucky enough to observe once: the black swan. On these outings, she takes great care not to encroach on nesting areas, or areas where biodiversity is fragile.

Cathy has been a nature lover ever since she was a little girl, "playing cowboys in the wild ". What could be more natural for her than to take an interest in and observe the sea and the sky? Meteorology, stars, clouds and, of course, "nature and animals" have a special place in Cathy's world. She lives a close relationship with the environment that surrounds her during her practice, a factor of personal equilibrium, which is essential to feeling well, according to her, and which makes her happy.

The third subject who can certainly be said to have an "environmentally friendly lifestyle" (Ibid.) is Jean-Christian. In addition to kayaking, he enjoys a number of outdoor sports and activities, such as hiking and cycling. We sense his attachment to the environment when he describes the "grandiose environments" and "incredible beaches" in Norway, and his respect for birds when he says that everyone should stay where they belong and not intrude on certain areas. Finally, the strongest indication is his vegetarianism, which he has implemented to minimize his impact on the lives of other living beings.

Among the elements we gathered from Gérard's interview, we couldn't detect any hint of an "environmentally friendly lifestyle" (Ibid.) other than his kayaking and love of the sea. Although he has "always lived as close as possible to the sea", being originally from Boulogne-sur-Mer, and considering it a "necessity", his answers are very factual (e.g. his definition of biodiversity is general, in line with the definition of the Office Francais de la Biodiversité) and he seems to consider the environment in which he practices as a support, "a horizontal plane without limits" that allows practice. Nor is he interested in traveling and hiking to discover other practice environments. Our three subjects, Geneviève, Cathy and Jean-Christian, therefore correspond to profiles that, according to Pelikán et al. Profiles that are attracted by the surrounding nature, that pay attention to others.

A taste for manual trades and tangible goods

Carfagna et al(2014) establish that high cultural capital - low economic capital can be linked to a "pro-environment lifestyle " 2, which seems to be the case for our subjects. Cultural capital tends to be downplayed, or reduced to the level of degree attained, as if we obtain higher cultural capital by staying longer in higher education (Serre, 2012). Yet our subjects have not been on the university benches for as many years as a PhD student. Pelikán et al. add to Carfagna et al.'s (2014) relationship that an ecological habitus tends to involve tastes focused on tangible, sensitive, local goods and manual labor.

One subject with a taste for manual labor and tangible goods is Gérard. In fact, he worked as an equipment technician for some thirty years after completing a BTS in mechanical engineering. An entire career in a manual trade after starting out as a draughtsman. Gérard has also passed two CAPs (vocational training certificates) in sanitary installation maintenance and community building maintenance. As well as a manual trade, Gérard also has a taste for DIY. He is a regular volunteer maintenance worker at Palavas Kayak de Mer, and has played a major role in building infrastructure to improve the club's management and life. Referring to Pelikán et al, Gérard would be one of the subjects with high cultural capital, as his tastes focus on more tangible, sensitive, local goods and manual labor. Manual labor is considered by Crawford (2009) to be a vector of intellectual emancipation, unlike so-called intellectual jobs, which tend to forget quality in favor of quantity. Gérard's intellectual emancipation through manual labor is a marker of high cultural capital.

The second subject who fits the profile established by Pelikán et al. is Jean-Christian. On the one hand, his hobbies. He told us he likes DIY, woodworking and manual labor. In fact, as an instructor at Palavas Kayak de Mer, he runs sessions to learn how to build a Greenland paddle (the traditional wooden paddles built by the first Inuit kayakers) and others to repair his kayak. On the other hand, Jean-Christian is no stranger to manual trades. Jean-Christian grew up in the countryside, on a farm, "in the middle of fields and woods". So he experienced nature on a daily basis from an early age. After working in the vineyards for several seasons, in the restaurant trade, and as a receptionist in a living museum, he worked as a tattooist in his own tattoo parlour for ten years. And he's currently a kayak instructor.

All our subjects seem to possess a high level of cultural capital, compared with less marked economic capital. Even if our subjects don't have "embodied" cultural capital (Serre, 2012) - although their ancestry should have been studied and questioned in greater depth - they do have cultural capital acquired, not through their studies, but through their lifestyle and passions. With this in mind, we're going to attempt to analyze the various behaviors, influenced or not by aquatic biodiversity.

A variety of behaviors

Contemplating

Contemplation. How can we fail to adopt this attitude when landscapes such as the Palavasian lagoons at sunset, mythical animals such as flamingos taking to the skies, or water stretching as far as the eye can see on the horizon. Cathy evokes contemplation. She uses the semantic field of vision, indicating a gaze on birds: "I love pink flamingos, cormorants and ducks". Contemplation is a behavior induced by aquatic biodiversity, but not a sign of its influence on kayaking. Indeed, everyone can be amazed by what they see while kayaking, without being aware of it and understanding that their actions can have an impact on their kayaking experience. We can define this behavior as passive. This behavior reflects Passavant's (2004) notion of an "enchantment of the world". We mentioned earlier that this feeling could appear on our kayak during sea or pond trips. It does indeed seem possible, and even happens regularly for Cathy, for example, or Jean-Christian when he crosses "grandiose environments" at the Pointe du Raz in Brittany, or between glaciers in Greenland. She had mentioned the contemplation of the environment, the feeling of freedom and the ability to breathe. The sea," she adds, "must be respected; it's sacred. This corresponds to the "symptoms" of enchantment with the world described by Perrin-Malterre (2007), which she describes as "wonder at the beauties of the world, a feeling of exaltation and inner quietude followed by bursts of affection".

Repair

Finally, Geneviève adopts a behavior of repair of the environment in which she practices. This behavior is not necessarily influenced by the presence of aquatic biodiversity, but Geneviève mentions pollution and lack of food as causes of the decline in animal populations present on the ponds and the Mosson. She points to the direct and indirect impact of mankind and therefore tries to make a modest contribution, during her personal outings and events organized by associations and NGOs, to improving the living conditions of aquatic biodiversity. More generally, litter-picking is a widespread practice among kayak groups, as they see biodiversity as an entity to be preserved, and water as an environment to be cleaned up if possible. She even adds that the impacts of kayaking are inherent in the behavior of the kayaker, not in the exercise itself. All that's needed, she concludes, is to raise awareness and teach good practices.

Avoid

This is perhaps the most complicated behavior to implement. It requires a certain amount of awareness and knowledge of the existence of forbidden zones and periods during which you can't sail just anywhere. It is therefore the behavior that requires the greatest investment, synonymous with the strong influence of aquatic biodiversity on the practice of our subjects. This behavior is adopted by all four of our subjects. Cathy tells us she avoids polluted areas on the Rhône-Sète canal. It seems to us that avoidance behavior can also be motivated by personal comfort, rather than by aquatic biodiversity. Gérard is very familiar with the problems associated with protected areas and nesting periods. He has revised a territorial document indicating all the species present in the Palavasian ponds, but does not show any intention of avoiding them during the interview. This raises the question of the intensity of commitment, and its limits. Our subjects' statements during the interviews are not subject to third-party control. As a result, the behaviours they report may be unconsciously or consciously exaggerated during the interview. However, he reminds us that we must not "have any impact on the environment in which we navigate". Finally, the Geneviève and Jean-Christian subjects are the ones who insist on the need to find out about authorized zones and ecosystems, so as to pay attention to nesting periods. These are the two subjects who seem most invested in avoidance behavior.

Primal exposure to nature

In order to understand the extent to which socio-ecological behavior reflects an ecological habitus among kayakers, we hypothesized that kayakers with a high level of cultural capital would develop more socio-ecological behavior than those with less cultural capital. We have seen that it is possible to develop cultural capital through acquisition, during our hobbies, while practicing our profession or through our lifestyle in general. By questioning the ascendants and other family ties of our subjects, we could have explored the transmission or otherwise of an innate cultural capital. What's more, the different behaviours described in our interviews may be limited by the territorial demarcation of our kayakers' practice, who mostly evolve on the same ponds, the same river and the same stretch of coastline. These behaviours, although shared by our members, may not reflect a general trend among kayakers in France, or even within the club. In fact, other behaviours are possible, such as non-modification by omission, non-modification because of lack of interest, or deliberate degradation due to a lack of knowledge of the environment. Other types of kayaking, such as those practised in artificial basins, on rivers or in competitions, will lead to other types of behaviour than those practised by kayakers in regulated recreational areas.

"People who care protect; those who don't know don't care" (Pyle, 2016). The personal alienation of humans from nature is, according to Pyle(ibid.), what leads to the ecological crisis. He denounces the "extinction of experience"(ibid.) of nature, through the disappearance of local species, or the superficiality of contact with it. So, in order to encourage improved behavior towards nature, the authors stress the importance of "critical consciousness" (Alexander et al., 2022). A deep experience of nature, even a bad one, is associated with "more positive behaviours and attitudes towards it "3 (DeVill et al., 2021), the result of a connection created, a learning in progress.

It therefore seems important to help citizens reconnect with nature, in order to envisage a sustainable world. This is what Palavas Kayak de Mer offers its members, tourists and schoolchildren, enabling them to navigate the Palavas lagoons and learn about ecosystems from our instructors. This approach is permitted and encouraged by the Syndicat du Bassin du Lez, which grants the club's kayakers right-of-way in a Natura 2000 zone that is off-limits to recreational boaters.

Bibliography

Alexander, N.; Petray, T.; McDowall, A. (2022), Conscientisation and Radical Habitus: Expanding Bourdieu's Theory of Practice in Youth Activism Studies. 2, 295-308. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2030022

Allag-Dhuisme F. et al (2016). The development of whitewater sports in France. Impact sur les milieux aquatiques. CGEDD report no. 009206-01, IGJS report no. 2015-I-27.

Bourdieu P. (1987). Choses dites (Les Editions de Minuit). Bourdieu P. (1980). Le Sens pratique(Les Editions de Minuit).

Carfagna LB, Dubois EA, Fitzmaurice C, et al. (2014) An emerging eco-habitus: The reconfiguration of high cultural capital practices among ethical consumers. Journal of Consumer Culture 14(2): 158-178.

Chang CC, Cheng GJY, Nghiem TPL, Song XP, Oh RRY, Richards DR, Carrasco LR. (2020) Social media, nature, and life satisfaction: global evidence of the biophilia hypothesis. Sci Rep. 2020 Mar 5;10(1):4125. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60902-w.

Crawford MB., (2009) In Praise of the Carburetor. Essay on the meaning and value of work. (La découverte)

DeVille, N. V., Tomasso, L. P., Stoddard, O. P., Wilt, G. E., Horton, T. H., Wolf, K. L., Brymer, E., Kahn, P. H., Jr, & James, P. (2021). Time Spent in Nature Is Associated with Increased Pro-Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(14), 7498. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147498

Dubuisson, N. (2009). Course - Les activités physiques de pleine nature - Quelles spécificités managériales, (p.1).

Ford, A. (2019). The Self-sufficient Citizen: Ecological Habitus and Changing Ford, A., Environmental Practices. Sociological Perspectives, 62(5), 627-645. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121419852364

Ibanez, L., Latourte, J. & Roussel, S. (2019). Pro-environmental behaviors and exposure to nature: an experimental study. Revue économique, 70, 1139-1151. https://doi.org/10.3917/reco.706.1139

Corneloup, J. (2007). Sciences sociales et loisirs sportifs de nature, éditions Fournel,

Kasper, D. V. S. (2009). Ecological Habitus: Toward a Better Understanding of Socioecological Relations. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/108602660934309846

Latour, B. (2006). Changer de société, Refaire de la sociologie. Paris, La Découverte.

Lazuech, G. (1998). Jean-François Bourg, Jean-Jacques Gouguet, Analyse économique du sport, Paris, PUF, 1998. Societes Representations, 7(2), 398-400.

Mounet, J.-P. (2007). Nature sports, sustainable development and environmental controversy.

Natures Sciences Societes, Vol. 15(2), 162-166.

Myttenaere, B. D., & d'Ieteren, E. (2009). Kayaking in Wallonia: At the crossroads of tourism development and environmental protection. Téoros. Revue de recherche en tourisme, 28(2), 9-20.

Passavant, E. (2004). Les conditions d'émergence d'un enchantement du monde chez les clients des

adventure tourism agencies. Paper presented at the second congress of the Société de Sociologie du Sport de Langue Française. Paris, Université Paris Sud XI, October 25-27, 2004.

Pelikán, V., Galčanová, L., & Kala, L. (2020). Ecological habitus intergenerationally reproduced: The children of Czech 'voluntary simplifiers' and their lifestyle. Journal of Consumer Culture, 20(4), 419-439. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540517736560

Perrin-Malterre (2007) Les sports de nature vus par la sociologie: état des lieux des recherches et perspectives.

Pociello C, (1981). Sports et société: Approche socio-culturelle des pratiques. Vigot.

Rech, Y., & Paget, É. (2017). Capturing transformations in nature sports through actor-network theory. Sciences de la société, 101, 48-63. https://doi.org/10.4000/sds.6137

Serre, D. (2012). Le capital culturel dans tous ses états. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, 191- 192, 4-13. https://doi.org/10.3917/arss.191.0004

Vautier, P. (2022). The influence of aquatic biodiversity on the behavior of PKM adherents. Master's thesis, University of Montpellier .

Vollet, D., & Vial, CATHY (2018). The role of nature-based recreation in territorial development: Illustration based on equestrian and hunting recreation. Geographie, economie, societe, 20(2), 183-203.

Wagner, A.-CATHY (2012). Habitus. Sociologie.

http://journals.openedition.org/sociologie/1200

1 Proposed translation for: "the embodiment of a durable yet changeable system of ecologically relevant dispositions, practices, perceptions, and material

2 Our suggested translation for "environmentally friendly lifesyle

3 Our suggested translation for: "more positive attitudes towards nature".